On 400th death anniv of great poet, playwright William Shakespeare

Augustin Sujan || risingbd.com

William Shakespeare

Mostafa Tofayel: In Kolkata, the then capital of Bengal, in 1915, there was a committee in observance of the 300th death anniversary of William Shakespeare, the all-time greatest poet-playwright. Also, a society called ‘The Shakespeare Society’ was formed on the same occasion. Dhaka University did not come into existence at that time.

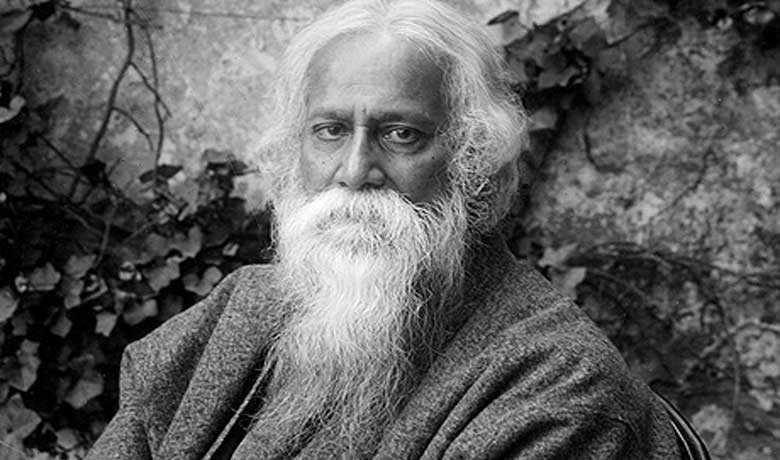

In today’s Dhaka, when it is the capital of independent Bangladesh, we do not see the existence of any such committee or society to commemorate the death centenary or anniversary of the greatest poet-playwright. It may be noted that William Shakespeare died on April 23, 1616; this month it dates back just four hundred years. In Kolkata, in 1915, a rich and colorful souvenir was published by the Shakespeare Society, in which Rabindranath Tagore contributed an elegiac poem, with Shakespeare in memoriam. We can look back at the elegy, composed originally in Bangla, and later on translated into English by the poet himself:

“When by the far away sea your fiery disc appeared from behind the unseen,

O Sun, England’s horizon felt you near her breast,

And took you to be her own. She kissed your forehead,

Caught you in the arms of her forest branches,

Hid you behind her mist mantle

And watched you in the green sward

Where fairies love to play among meadow flowers.

A few early birds sang your hymn of praise

While the rest of the woodland choir were asleep.

Then at the silent beckoning of the Eternal

You rose higher and higher till you reached the mid-sky,

Making all quarters of heaven your own.

Therefore at this moment, after the end of centuries

The palm groves by the Indian sea

Raise their tremulous branches to the sky

Murmuring your praise.”

I recall my university days at Rajshahi University during seventies when, as renowned personalities as professor Zillur R ahman Siddique, professor Ali Anowar, professor Dr. Sadruddin Ahmed and professor Ahmedul Haq Khan had been our teachers of English literature. I remember those my favorite teachers’ style of giving us classes on Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Julius Caesar, Macbeth, Tempest, As You Like It, Measure For Measure, Troilus and Cressida, King Henry The Fourth, The Sonnets and so on. We enjoyed their broad detail interpretation of Shakespeare. The zeal and fervor and enthusiasm encapsulated in us so much so that we got imbued with the spirit and pride of reading Shakespeare. It was out and out “A thing of beauty and a joy forever.” During those days, Professor Z.R. Siddique was doing his works of Bangla translation of Shakespeare’s sonnets. Encouraged and infused with their enthusiasm, of late, I have ventured to do the Bangla translation of Shakespeare’s sonnets solely out of pleasure.

Shakespeare’s sonnets have been translated, in Bangladesh, by poet Professor Zillur Rahman Siddique, poet Mohammad Nurul Huda, poet Selim Sorwar and others. Poet Selim Sorwer’s translation in Bangla is faithfully literal, from the reading of which I have made my comprehension of the sonnets to the best and most. It is notable that in Shakespeare studies in Bangladesh, sonnet 18 is, most often, given the highest importance. I have made close observation of the sonnets’ various themes and found that there are, at least, thirty very representative and thematically important poems in Shakespeare’s sonnet sequence. However, out of the bunch of Bangla translations of sonnet 18, the one done by poet Mohammad Nurul Huda, has appeared best to me.

Shakespeare’s Sonnets, provide the record of Shakespeare, the man

In the plays, The Tempest and The Tragedy of Hamlet in particular, there are objective glimpses about the mind of Shakespeare. But in the sonnets, the readers may get at Shakespeare as a speaker, who has expressed his painful honestly, his art of writing and his professional standing, his friendship and his love etc.

The speaker is a persona or character in the sonnets, of Shakespeare. He figures to be almost transparent in every poem to a revealing degree. The sonnets concern four characters--the first one, the “I”, speaking in these poems can be taken to be autobiographical in a degree which the plays cannot. In truth, the speaker, “I”, does identify himself as “Will” in a witty pair of sonnets--135, 136. Harold Bloom assesses the complex presence of the author in these terms:

“Selfsame with Shakespeare he is not, yet he lingers near Shakespeare, and fascinates us by that proximity.”

The critics have said that the speaker “I” in the sonnets speaks with a fairly consistent voice throughout the sequence. Firstly, he is an older man who addresses a friend as “Young” repeatedly. We hear in sonnet 62 that the speaker is “Beated and chopped with tanned antiquity.” In sonnets 71 and 73, the speaker broods on the “winter” of his life and contemplates the world after his death, a world in which the Young Man will still live. These poems give an impression of a serious illness of the speaker or the imminent prospect of his death, and also the impression that he is mainly a melancholy lover and possibly struggling with self-pity as well. We get the impression that he has endured trials in life. We might point to sonnet 29-

“When in a disgrace with Fortune and men’s eyes

I all alone beweep my outcast state,”

Or to sonnets 66-

“Tired with all these, for restful death I cry

As, to behold desert a beggar born,”

Or to sonnet 37-

“As a decrepit father takes delight

To see his active child do deeds of youth

So I, made lame by Fortune’s dearest spite”

Which seem to combine the topics of old age and misfortune. Likewise, sonnet 93’s phrase “Like a deceived husband’, leads readers to presume that Shakespeare’s wife, Anne Hathaway had been unfaithful to him. It leads also to presume why he was enamoured with a youth and sleeping with a Dark Lady. Some sonnets even express an outraged hurt of betrayal, such as sonnets 40-42, or the recognition of falsehood between lovers, as in sonnet 138 or 151.

In sonnet 23, the speaker alludes to what may possibly be taken as Shakespeare’s career as an actor (“As an unperfect actor on the stage”). In sonnets 110 & 111, his going “here and there” may represent his work as a travelling actor, one who has “made myself a motly to the view” and “thence my nature is subdued/To what it works in, like the dyer’s hand.” He mentions his “Muse”, his “pen” and “ink”, and his struggles in writing. There also seems to be a genuine anxiety about a Rival Poet, expressed through the sonnets 76 to 86. And this leads to the assumption about a possible patronage relationship between wealthy noble men and the poor poets. The speaker calls himself a “slave”, which is a statement of his subordination.

John Shakespeare`s house, believed to be Shakespeare`s birthplace, in Stratford-upon-Avon.

The Young Man is likely the recipient of most of the sonnets 1-126. These sonnets address a “Thou” in the second person. A few more narrative sonnets are there in the third person which allude to the same person or character. There is an exceptional warmth of address and intensity of situation dramatized in these sonnets, and these qualities have made the readers assume a historical recipient behind the sonnets. The recipient has become known as the Young Man.

The Young Man is the one to whom the speaker appeals in the first 17 “Procreation” sonnets. Some critics hypothesize that Shakespeare may have been commissioned by concerned parents to write these poems in view to convince their son to marry and have children. We hear of this youth in sonnet 2, in which we learn that he, the Young man is “Most rich in Youth”. Sonnet 22 declares that “Youth and thou are of one date.” Sonnet 41 speaks of chiding the Young Men’s beauty and “Straying youth”, while sonnet 96 broods on the man’s youth being a source of his faults and wantonness. By contrast, the speaker in sonnet 73, lies “On the ashes of his youth”, though, at times, the Young Man’s loveliness and the speaker’s desire have a shared identity: “Our undivided loves are one” (36); “Thou mine, I thine, eternal Love” (108); and also sonnets 18, 31, 36 and 39. The finishing couple of sonnet 18 reads;

“So long as men can breathe and eyes can see ,

So long lives this and this gives life to thee.”

Sonnet 116’s famous defense of the “marriage of true minds” appears, by context, to be addressed to the Young Man. In sonnet 20,

“A woman’s face with Nature’s own hand painted” the speaker playfully suggests that the youth has very attractive and feminine features, and Nature went too far and gave the young Man “a thing”. Otherwise, the speaker prends, he would have been the perfect lover. Some critics have found the comment “master-mistress of my passion” as something shocking, since it indicates to the speaker’s homo-sexuality. The relationship seems to have been intense enough that the Young Man’s “sweet love” sustains the speaker during hard times (29).

Sonnets 40-42 dramatize a social scandal that many take to be the Young Man’s cheating on the speaker with a woman known to them both. The woman is none but the Dark Lady of the last series of sonnets. It is worth noting that even in the face of cheating by the Young Man, the speaker keeps on speaking of his beauty in sonnet 41 with a sort of obsession. In sonnet 144, the speaker frames himself as tempted by two loves where “The worser spirit a woman colour’d ill,” “the better angle is a man right fair”.

The speaker idealizes the Young Man’s beauty in a penchant manner. Sonnet 68 promises that the youth’s beauty is made “To show false art what beauty was of yore”. Moreover, the Young Man’s beauty becomes Nature’s treasure and serves as a measure to indicate natural abundance. Shakespeare’s idealizing of youth goes on when he says in sonnet 95-

“Thee,/Where beauty’s veil doth cover every blot /And all things turn to fair that eyes can see!”

Bud subsequently we observe, the idealization does not last long. In spite of the veiling of the blot, the speaker has a wounded memory. The speaker knows that this relationship is far more complex and the Young Man is far less ideal, not to mention far less loyal and trustworthy.

This insecurity may have a lot to do with the Young Man’s apparent social standing. Sonnet 37 speaks of “beauty, birth, or wealth, or wit” being “Intitled” in thy parts”. The word “Intitled” is precisely chosen for the addressee is from the landed aristocracy. The speaker chastises the Young man for adding a curse to his “beauteous blessings” in sonnet 84, since he is acting ungentlemanly in “Being fond on praise”, or worrying two much about his reputation among the general classes. And certain sonnets do indicate that the Young Man has some public standing, eventually the speaker boasts that his love “all alone stands hugely politic”. By “politic” the speaker means prudent or wise, since daily fortunes will not sway his love.

These clues in hand, it is not surprising to consider the Young Man pattern to have been the two active Elizabethan Young Man-the Earl of Sounthamton and the Earl of Pembroke. Anyone of the two, or both of them could be the recipient or recipients of the address that Shakespeare has made through his sonnets.

By this way, the sonnets provide the readers a good deal of information about Shakespeare’s life at close quarters, rather tahn from historical assumption and hypothesis.

The Dark Lady sequence

The Dark Lady is the character whom Shakespeare’s speaker turns to after the sonnets to the Young Man. This new addressee surfaces in sonnet 127 and remains uptil the end. Although Shakespeare provides no explicit clues, it is just possible that the Dark Lady enters the sequence in sonnets 40-42, which dramatize a crisis in the speaker-Young Man relationship. In those three sonnets, the Dark Lady is the object of the “robbery” by the “gentle thief” that the Young Man is. It is the Dark Lady who becomes the temptress of the Young Man’s “Straying Youth”.

Having arrived at a kind of closure with “my lovely boy” in sonnet 126, the speaker turns in sonnet 127 to a changing measure for beauty. Once things “fair” or “light” were considered beauty, “But now is black beauty’s successive heir/And beauty slandered with a bastard shame”. We next hear about the speaker’s mistress having eyes that are “raven black”, her breasts “dun”., her hair “black wires”. Critics have taken these details as signs of the Dark Lady’s dark complexion. In sonnet 127, Shakespeare asserts that blackness is not beautiful, but the present age thinks it so. It is the first sign of a growing misogyny towards the Dark Lady.

Shakespeare`s Dark Lady, as imagined by the artist Neville Dea Photograph: Bbridgeman Art

Sonnets 128-130 display a breathless range of tone and expression about woman. The first one is a charming poem of physical desire, based on the popular Renaissance tableau of a woman playing the virginal. In the poem, a piano-like instrument is presented as a metaphor in the context of the Dark Lady, meant with heavy irony. Sonnet 129 describes sexual appetite as an irrational enslavement. The speaker frames the woman’s sexual attractions as a “heaven that leads men to this hell.” In sonnet 129 the speaker sets off “my love” from “any she belied with false compare”. But this final phrase reintroduces the themes of duplicity, misleading desire and false representation, whether by cosmetics or anything.

The speaker seeks to be a sacrificial stand-in for his friend in 133. But in sonnet 134, the Dark Lady has not set free the Young Man from his own passion:

“Him have I lost, thou hast both him and me;

He pays the whole, and yet I am not free.”

The woman stands accused of double-crossing the male lovers, at both of their expenses. Sonnets 135-137 are some of the bawdiest in all of the sonnets which Shakespeare has employed to colour the Dark Lady. Neither heart nor soul of ideal lovers, but “Will will fulfil the treasure of thy love, Ay, fill it full with wills” -adds the speaker coarsely, and in a vulgar language, to mean how abominable the person aimed at.

Sonnet 137 is yet coarser, the speaker’s frustrating sense is further expressed in sonnets 139-142, where the speaker denounces the Dark Lady’s unkindness.

Sonnet 143 presents mother-and child simile which implies a situation in which the Dark Lady is interested in another lover leaving the speaker, “thy babe”, who chases the woman and begs her to turn back. Sonnet 144 re-established the triangle of love between the speaker, the Dark Lady and the Young Man. In that triangle, the speaker shows his favour to his friend that is the “better angel” providing him with comfort, and the woman “a worser spirit” who is coloured ill, and is the love of despair. In sonnet 146, the speaker wishes to move forward beyond the confines of the body and its desires and looks towards the eternal peace of the soul, beyond Death. In Sonnet 147, the speaker accuses his “cunning love” of keeping him in tears, since it prevents his eyes from “well seeing” and finding her “foul faults”. Sonnet 150 presents a paradox: the speaker is increasingly devoted to the woman whom “the more I hear and see just cause of hate.” In sonnet 151, the speaker admits his enslavement to flesh-“I do betray/ My nobler part to my gross body’s treason”. The last poem of the Dark Lady series, Sonnet 152, informs us that the Dark Lady is, in fact, an adulterer. The two last poems-153 & 154 are symbolic ones on the basis of Cupid myth.

In the sonnets, Shakespeare’s choice of colour to identify his mistress is an exception from the tradition. Not only that, by so doing Shakespeare has introduced into his poetry rather complex issues about culture, nationhood, race etc. Shakespeare’s London, Shakespeare’s times and Shakespeare the man are made known to us through the sonnets.

The Rival Poet Theme

In each and every major aspect of the sonnets, there is a crisis in the speaker’s self-confidence. In spite of the deep friendship that the speaker has to establish with the Youth Man, even to the extent of immortalizing it through the lines of his poems, there looms large the crises of self-confidence and betrayal. Again, in spite of the speaker’s unflinching physical love for the Dark Lady, frustration owing to her treachery and adultery, shocks him pathetically. Again, the speaker-Young Man-Rival poet triangle marks Shakespeare’s sequence and mars the speaker’s peace of mind.

The “alien pen” of the Rival Poet alienates the speaker from the Young Man’s affection. Sonnet 76 indicates a self-doubt in the speaker that the rival’s subsequent appearance only heightens. “Why is my verse so barren of new pride”, the speaker asks of himself. He asks, why is it out of fashion and a stranger to “New-found methods and to compounds strange”? Yet the second half of the sonnet offers a resolution: “You and love are still my argument.” The speaker puts a new dressing on old words that reflect the consistency of their relationship.

The speaker acknowledges that the Young Man has encouraged verses not solely from him but from “every alien pen”. To mean a field of poets, the speaker uses metaphor in the form of invaders who are vying to take over his accustomed “use”, meaning his poetic activity. In the third quatrain of the sonnet the speaker singles himself out as the superior and more loyal poet. He appeals to the Young Man to be “most proud” of him. But the Young Man’s virtues inspire all of the poets. In sonnet 79, the primary anger of the speaker is at his having been once exclusively the Young Man’s poet and now having competition. The particular poet who makes the speaker feel inferior is called the “Worthier pen”. In sonnet 80, he becomes a better “spirit”. But the speaker accuses that the Rival Poet is a fake and even a thief. Taken equally, the speaker concedes that the Rival Poet’s praise threatens him “tongue-tied”, and he judges himself “inferior far” compared with his competitor.

Sonnets 116 also speaks of the Young Man’s worth who must “seek anew/Some fresher stamp of the time-bettering days.” The Young Man finds in the rival’s poetry something fresher and more fashionable than that of the aging speaker. In the lines of the sonnet we obeserve that the older poet finds the rival’s attractions dubious and full of “Strained touches” and “gross painting” and no match for his own “true plain words.” Sonnet 83 attempts to isolate the triangle by mentioning to the Young Man about the rival poet and himself as “both your poets.”

The critics have found the opening lines of sonnet 86 to be a clue to the Rival poet’s style of verses:

“Was it the proud full sail of his great verse?”

In 1874 William Minto first suggested George Chapman as the likeliest candidate for the Rival poet. And Chapman remains the most valid choice till today. But almost every poet contemporary to Shakespeare, has been put forward, such as Christopher Marlow, Ben Jonson, Samuel Daniel and Edmund Spenser. Chapman, the translator of Homer, fits best with the speaker’s defeated appraisal, and Chapman’s work Shadow of Night may have been alluded to in the later lines of sonnet 86. The speaker says that it is the approval and inspiration of the Young Man which has made the Rival Poet sail “full”. On the contrary, the speaker contends that he himself lacks “matters” that is poetic content.

The sonnets in this sequence express the speaker’s painful honesty about his art and professional standing, his friendship and his love. The sonnets, as such, stand out as the records of the social and mental condition in which Shakespeare has continued his pursuit of composing verses and plays. This honesty on the part of Shakespeare provides the reason why so many readers through the centuries have found interest in the sonnets instinctively.

Sonnet 3: The Procreation Theme

Following sonnet 1 & 2’s persuasion, the third sonnet returns to a more direct command: “look in thy glass”, the speaker says. By imploring the young man to look at himself in mirror, or “glass”, the speaker hopes to make him realize how others feel when they see the Young Man’s beauty. Then, perhaps, he will understand that “Now is the time that face should form another.” Seeing himself, as if, from the outside, maybe he will see how his beauty is fragile and transient. If he does not reproduce and create an heir, he will “beguile the world”, meaning cheat the world, and will “unbless” a mother who could bear child. The speaker insists that no woman would turn down a chance to conceive a child with the young man.

At this stage of his persuasion, the speaker steps forward with an agricultural metaphor much common at that time. The speaker says that any infertile place would welcome the young Man’s “tillage” or ploughing; any woman would desire his “husbandry”, meaning farming. The word “husbandry” implies that the young Man should become a good husband as well who fulfills his wife by giving her children. The 7th and 8th lines of the sonnet attempt to accuse the young Man. In these lines the speaker says that if no woman would reject a proposal of union with the Young Man, why he, on his part, would forgo children or posterity? In doing so the Young Man would show his narcissism or “self-love” and that would lead to his deathly consequences. His own body will become his tomb, with no separate tomb to commemorate him.

In the third quatrain of the sonnet, the speaker comes up with another plea. He says that he, the Young Man, is actually a mirror to his mother. His (the Young Man’s) youthful beauty calls back her mother’s spring like youth. The “lovely April of her prime”. He, too, will one day be old, with wrinkled face and diminished eyesight. The speaker again goes on in sighing that by having children now, as his mother did, he will be able to see his own “golden time” in future, when old age will attack him, too.

In the concluding couplet the speaker gives a solemn warning to the young Man. He says that if he (the Young man) stays single, surely he would “die single”, and in dying so, the memory of him would utterly die.

The sonnet offers a drama of self-Knowledge by introducing the metaphor of mirror in the sonnet. In an admonishing tone, Shakespeare’s speaker continues to say that the young Man’s situation is “darkly”. He (the Young man) will soon lose his own fresh face, and will have no consolatory face in the person of his child, to appreciate him and reflect him.

Sonnet 64: Time, The formidable enemy

Sonnet 64 is about a lover’s anxiety – the anxiety which has posed an emotional crisis, repeated throughout Shakespeare’s sonnet sequence. That enemy is not the capricious, the faithful patron or the unfaithful friend- Young Man, but time itself. It is Time, “the Devourer, evoked specifically in line 5 of sonnet 64, in the image of the “hungry ocean”. As “hungry ocean”, Time will eventually consume all things- even young, beautiful and beloved things.

We notice the monosyllalic opening of sonnet 12:

“When I do count the clock that tells the time” Which sounds the rhythm of time as a personified threat against the Young Man. About his friend, the Young Man- the speaker fears that “thou among the wastes of time must go”----- and asserts that the young man is already going there. The concluding couplet of this poem brings home this grim theme:

“And nothing against Time’s scythe can make defence

Save breed, to brave him where he takes thee hence.”

There is no defender to stand before Time’s scythe, but one’s own son. Time’s scythe undefended will appear as grim reaper cutting down all living things.

In sonnet 15, the enemy of the Young man is multiplied as Time and Decay debate with each other as to when his life will be extinguished. In sonnet 16, time is a “bloody tyrant”. In this sonnet, the poet recommends that the young man’s “own sweet skill”, that is his abilty to “draw” himself in the form of his son, can save him from the hand of the tyrant. In sonnets 17 and 18, the poet imagines that his rhymes being read “in time to come”, as well as through his possible child, the youth would live twice. Again in sonnet 19, “Devouring Time” re-emerges.

“Devouring Time” blunt thou the lion’s paws,

And make the earth devour her own sweet brood;

Pluck the ken teeth form the fierce tiger’s jaws,

And burn the long-lived phoenix in her blood”.

The poet’s war with time returns again in sonnet 55. Here, the poet asserts, his “powerful rhyme” will outlast marble and monuments. The Roman poet, Horace, famously said in his Odes, “I have finished a monument more lasting than bronze”. Shakespeare’s speaker in the sonnet appropriate the Resurrection itself and says that his friend will live in his poetry and in lover’s eyes “till the Judgement”.

Sonnet 64 begins with:

“When I have seen by Time’s fell hand defaced“.

“Fell means savage or deadly. The monosyllables used by Shakespeare in the opening line appear pounding, providing a violent and rhythmic effect. The second line is a gem of Shakespearean compression and implication. The “lofty towers“ in line 3, where “sometime” means once, are now “down rased” or “razed”. The two words together, perhaps means to add an intensity of meaning: not just falling down, but a crashing down spectacularly. This image of fallen towers is a reference to the England of Shakespeare’s own day. The destruction of abbeys and monasteries during the reign of Henry viii, left a lasting, ruinous mark on the post- Reformation English landscape.

In the next quatrain of the sonnet---

“When I have seen the hungry ocean gain

Advantage of the kingdom of the shore”

...............................................................

..............................................................

When I have seen the hungry ocean gain

..............................................................

When I have seen such interchange of state”

..............................................................

Shakespeare places dependent clauses, “When --- when---- when--- when----“ across the poem. This is a time-factor. The couplet at the end comments on “this thought” that has just occurred. In the second quatrain we observe that Shakespeare has employed military image: “gain” /”Advantage”, as if certain general is attempting to conquer a territory from his foe, meaning the march of time proceeding unabated.

Short biography

Mostafa Tofayel , is, at present, an adjunct faculty of English department, European University of Bangladesh, Shyamoli, Dhaka.

He is the author of the only Bengali epic poetry entitled ‘Akjon Prometheus Tini’, based on our independence struggle, 1971. He is the translator of Omar Khaiyam’s ‘Rubaiyat’, Shakespeare’s Sonnets and Rabindranath Tagore’s ‘The Stray Birds’. He has a good deal of publications on the history of Rangpur and Kurigram. Now he lives at Rangpur.

In Dhaka, he is known for his essays on literary criticism and his poetry. In the elite cultural programs of literary recitations, eminent recitation artist Bhaswar Banerjee of Dhaka has chosen mostly from his epic,’ Akjon Prometheus Tini’. He is known in Dhaka and Kolkata equally for this book.

risingbd/DHAKA/June 28, 2015/Augustin Sujan

risingbd.com